Food Is the Hero--Not the Villain

Food, says the former New York Times critic, can make trouble and can make pleasure-- but mostly pleasure.

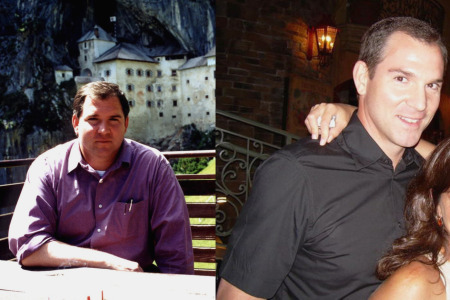

Image Courtesy of Frank Bruni

Formal and informal reactions to a book start trickling in weeks and even months before its publication, and the ones to Born Round , my memoir, which just went on sale, have often surprised me.

I've been told I've done a service for people with eating disorders, by admitting and describing my own experience with self-destructive behaviors. And I've been told I've misled readers about the gravity of bulimia, because the period during which I threw up meals was relatively brief and I was able to stop without therapeutic help.

I've heard or read that my story holds lessons and hopes for overweight overeaters, and I've heard or read that by treating extra pounds as a source of unhappiness and pain I've bought into and perpetuated the idea that girth and mirth are incompatible.

I understand all of these perspectives. But they've surprised me, because when I decided to write about my turbulent relationship with food and when I later buckled down to the actual writing, I wasn't trying or not trying to make a given statement about eating disorders--or even to diagnose myself as having or not having a particular one. I wasn't trying or not trying to exhort the world's overeaters to a reckoning and to reform. I was just telling my story as truthfully as I could. There wasn't much attendant calculation, and there wasn't a real agenda.

Scratch the final half of that last sentence, or rather, amend it. There was some agenda, which was this: to promote my belief that a great many people, including those of us with a professional focus on food, have food secrets, food anxieties, and complicated relationships with food, which we love but don't always manage properly.

Most of the books I'd read by professional eaters didn't broach this. They described purely romantic, joyous experiences with food, seldom acknowledging that food can be enjoyed in excess and that eating can become an unhealthy compulsion--not unlike a drug addiction.

I wanted to get that point across, and I wanted to describe how after many turbulent decades I moved from a needy, wary, resentful, heedless, and deeply fraught relationship with food to a much, much smoother one. I wanted to recount how I ballooned to around 270 pounds--I'm just under 5-feet, 11-inches tall--and then fought to get rid of more than 70. I wanted to do that in part because I thought the lessons I'd learned along the way could be instructive not just to other overeaters but to anyone and everyone trying to integrate a sizeable appetite with a desire to stay healthy and reasonably trim.

But what I wanted more than anything else was to tell a good story. The overarching impulse behind this book wasn't an overeater's impulse, or a bulimic's impulse, or a fitness guru's impulse. It was a journalist's impulse. Upon reaching the richly ironic destination of restaurant criticism, I looked back and realized that my swerving, lurching, roller-coaster journey to get there might make for an interesting narrative. I realized that it had a clear theme: an obsession with food I had to wrestle control of and channel in a healthier direction.

NEXT :

PAGES :

In writing the book, I tried to make that theme the organizing principle--the factor that governed which episodes and incidents from the past, along with which friends and family members, would take center stage. One of the greatest difficulties I encountered was determining how often, and for how long, I could and should digress from the subject of eating. Eating was the big, main river. If the tributaries were many and frequent, would the larger landscape come to seem incoherent?

I fiddled as I tried to figure that out, cutting out whole periods of time and lengthy anecdotes, then adding some of them back, then taking a few away again, then just scratching my head. There was a long riff on the sad and comical fates of the various dogs in my family's life: it ended up on the cutting-room floor. There remains a long riff on a stupid email joke at Newsweek magazine that spawned the rumor that Mary Tyler Moore had died. Maybe it shouldn't be there.

Writing a memoir is strange that way: there's no right, no wrong, a dozen different opinions from a dozen different friends, and an ultimate acknowledgment by all of them that only you can decide what to lose and what to keep because it's your story--such a deeply, deeply personal thing.

A few of those friends and a few of my relatives asked me, as they read the manuscript, if I was sure I wanted the book to be quite as personal as it is. Some early reviews have said that the book includes a few revelations too many. My thinking as I laid bare my saddest and craziest moments was that I should hold myself to the same standard I've always tried, as a journalist, to hold profile subjects to. I should demand full candor, specific details--the works. I've urged that on people I've profiled, because their stories usually wind up more compelling and amusing that way. So I urged it on myself too.

I've been asked if I was and am concerned that some of these revelations--that I feared food in the past; that my binges didn't discriminate between good and bad food; that I was long fixated on quantity as much as quality--cast the reviews I wrote during five-plus years as the Times restaurant critic in a different light. I'm not sure how to respond to that, because I'm not sure what exactly the questioners mean.

Are they suggesting I was more favorably inclined toward restaurants that hurled fewer calories in my path? Reflecting on hundreds of reviews, I don't see that pattern.

Are they suggesting I approached restaurants and eating with a trepidation that somehow colored what I wrote? I don't see or sense that in the hundreds of thousands of words I filed, but readers would be better judges than I.

I like to think that my ability, after such a turbulent history with food, to do the critic's job for five years and to stay in good health, at a steady weight, meant an extra measure of joy in the job I was doing--a particular kind of celebration. I see food, in the end, as the hero of the story, not the villain. Conveying that was the trickiest aspect of this book. I remember breathing a huge sigh of relief when the writer Tom Perrotta emailed me a blurb for the back cover that said that reading the book made him hungry. I hope it makes other readers hungry too.

PAGES :