The Mystery of the Vanishing Bees

The author's family takes up beekeeping only to have their colony nearly killed off. What happened?

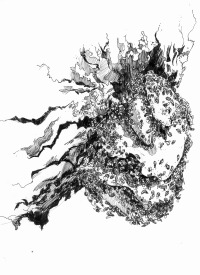

Illustration by Miguel Jirón

It started, as most beekeeping stories must, with a hive. It was our hive, so far as a wild--that is to say, un-kept--hive could be. It was at the bottom of our driveway, and I walked, ran, biked, and eventually drove by that hive nearly every day of my life until I was 18 and left home. One time, on a dare, I threw rocks at it, though I didn't really want to.

We had a good relationship with those bees; I never got stung. My parents respected them and I respected them, too. So when a neighbor began to complain and finally threatened to call an exterminator on the hive, my father called a beekeeper to help him figure out what to do.

Paul "The Bee Man" Cronshaw is a high school biology teacher and backpacking enthusiast who eats poison oak leafs to build up an immunity. He has been keeping bees for 30 years, even though his wife is deathly allergic and doesn't even like honey.

Cronshaw is, as far as I know, the finest bee-man in all of Santa Barbara. So he assessed the situation. Not long after I got a call. "We're keeping them," my father said. "Paul's going to come over tomorrow and set up the boxes. He'll move the hive onto our property. Mom and I are going to be beekeepers."

That was two years ago. In that time nearly half of all honeybees in North America have vanished. The culprit is a phenomenon known as colony collapse disorder (CCD). It's an X-Files -worthy mystery, with entire hives disappearing in broad daylight, bees dying midflight, and no known cause.

Many researchers were quick to blame the varroa mite , which wiped out 45 percent of honeybee populations in late-1980's and '90's. But mites leave evidence, and there was little trail to follow with CCD. Some thought it could be a virus; others blamed radiation from cell phone towers; still others claimed, perhaps appropriately, alien abduction.

Illustration by Miguel Jirón

What we're learning now--detailed in a paper published in Scientific American --is that there is no single cause of CCD; that the disorder is not one problem but many working in concert to undermine the very social and physiological fabric of hive society. As Andrew Coté, co-founder of New York City Beekeepers, told me recently, "Asking to explain what causes CCD is like asking what causes poverty."

The silver lining to the CCD disaster is the media coverage, and public outcry, that have followed. Bees probably hit their lowest point in the American consciousness in the early 1990's--the mite disaster wiped out nearly half the population, then Africanized "killer" honeybees invaded, then Macaulay Culkin's character in the film My Girl died from bee stings. Nobody really cared for bees back then.

But it's 2009. We've gone green, and bees are having a moment. Haagen Daz started a campaign to raise awareness for all that bees do for us (such as adding honey to Haagen Daz ice cream), and bee-lovers have a Twitter feed called Tweehive , in which participants attempt to "replicate as closely as possible the behavior of a beehive."

The actual purpose of both efforts--beyond selling ice cream and spreading bee love--is hard to parse. What's more important, for the bees at least, is the extraordinary rise of full-blown backyard beekeepers: from New Yorkers keeping bees on rooftops (Coté: "It's a bandwagon to jump on, just like after 9/11 everyone threw an American flag on everything."), to the Obama's hive and vegetable garden, to my parents' casual bee-rescue.

NEXT :

PAGES :

So I'm hot, but also worried.

"It's stress, generally speaking, that's blame for these die-offs," Cronshaw continues. "If you lived in one of these boxes and traveled all around the U.S. and were fed one monoculture after another, you'd be stressed, too. This is low stress because they're staying in one place." Plus, I tell myself, we're in California.

How wrong I am. For most bees that see the Golden State, California is work. Roughly two-thirds of all honeybees in the country are brought through the San Joaquin Valley to pollinate its flowering crops. Some are schlepped over from as far away as Australia. This is the bee's (or more specifically, the beekeeper's) bread. The vast majority of the money made off honeybees is not from their honey but through pollination. Some estimates place the domestic bees-as-agro-pollinators industry at around $30 billion annually.

"If you move your bees tens of thousands of miles a year in pursuit of pollination profit," Coté told me, "well, let's just say a lot of these commercial beekeepers are having their chickens come home to roost."

Cronshaw and Coté seemed to make sense--if CCD was killing mostly commercial bees. But if that were the case, why was I standing here with a rapidly swelling hand attempting to save a nearly empty hive?

Illustration by Miguel Jirón

My parents' beekeeping began with a bang. The hive was healthy, robust. So robust that it quickly doubled, created a new queen, and my parents went from one hive to two. The new hive was going gangbusters, and my father expected a bumper-crop of honey in the very near future. It was just as he was preparing for the laurel sumac and toyon blooms when the new hive went very quiet. When he opened it up, the scene was devastating: few bees, minimal honey. Ants and moths had invaded. Soon after, I flew into town (not so much for the bees, but to visit my folks), and Cronshaw came by to investigate.

"This hive has no queen," Cronshaw says. "It's called a lame worker. When we split the hives and brought the daughter over to this new one, well, she must've been a dud." He's got his bare hands in the thing and a few, listless bees are crawling over them. I ask if this could be a case of CCD. It's not. It's simply a case of kept bees making a dud queen.

But Cronshaw has brought a new queen and enough of her subjects to repopulate the hive. He rescued these bees from somebody's wall, which is how he spends a lot of his free time these days, as people move away from outright eradication and toward bee-rescues. These wild bees are healthy, and will likely take to this hive like my parents' original wild set. It's important that they're out there, these wild bees, because CCD hasn't affected them nearly as much as kept ones.

Even though the European honeybee, Apis mellifera , has been domesticated for millennia, CCD is a 21st-century phenomenon--with its many causes ranging from current farming practices to modern trade routes. "The growing consensus among researchers," the Scientific American article concludes, "is that multiple factors such as poor nutrition and exposure to pesticides can interact to weaken colonies and make them susceptible to a virus-mediated collapse."

The virus in question was an import, from Israel. But the more serious concern is that any new virus can come in and wreak havoc on our over-stressed, malnourished bees, and it's not possible to vaccinate. What we need, then, is a little bit more bee understanding, appreciation, and tolerance. And what we really need are more wild bees. Which brings me back to that tree at the bottom of my driveway.

There's a notch in the tree, quite low, where the old oak splits in two and branches outward. The notch is hollow: it's a bee-tree, a near perfect hive habitat. It only took a few months after my parents' bee-rescue for a new hive to move in. By then CCD had struck North America, bees had had their moment, and the neighbors who once considered them a nuisance decided, wisely, to let the bees be.

Months after my trip out west I received a large mason jar full of our honey. Honestly, it probably didn't taste a whole lot better than a lot of the high-grade, farmer's market honey that's made by other relatively happy, sedentary bees. But to me this honey was magical. It tasted like home.

PAGES :