About My Father

My father might have saved himself from a severe stroke; NPR took note, and someone in your life might want to, too.

Update: Five years after I wrote this piece about my father's presence of mind in asking to be given t-PA within two hours of what he immediately and correctly diagnosed as a stroke, he kept feeling for the bottle of nitroglycerin he long carried in his shirt pocket. He was again correctly diagnosing himself, this time knowing that the chest pain and shortness of breath he felt signaled either an attack of angina or an oncoming heart attack.

This time, though, the ending was less happy, and final. For ten days he had been experiencing symptoms of what turned out to be an underlying advanced pneumonia, which lowered both the amount of oxygen in his blood and his blood pressure. When a visiting nurse who luckily was at our house at the time obtained a fresh tablet of the "nitro" he was asking for, his pain vanished. But his blood pressure fell precipitously, and he died.

As endings go, this could hardly have been more fortunate. The visiting nurse was present because my stepmother, physician brother, sister, and I had decided after putting my father on palliative care--which has a new meaning in medical circles, that is doing everything possible to prevent re-admissions for chronically ill patients, while continuing to test for and treat reversible ailments--to move to hospice care at home. This still has the commonly understood meaning of “hospice”: no new medical investigations or treatments, and no new medications except for pain. Morphine had been ordered for the next day.

Just an hour before, when I spoke with my father to say I was on my way to visit, the nurse reported that he was laughing and smiling as he sipped his morning coffee. My brother had spoken with him by video chat the previous evening; my sister and niece were video-chatting with him via his caregiver's phone when they thought he went to sleep. In fact he had died. Minutes before, while waiting for the nurse to find the fresh nitroglycerin, my father had been laughing at jokes my funny, cheerful stepmother was making.

However peaceful, a death is final, and as is usually the case with someone so close, that finality has yet to register. While it does, here are the remarks I made at his funeral. I offer them not only out of the love I felt for my father but as a tribute to a kind of caring in medical practice that is harder and harder to find--because it is harder and harder to practice, as my superbly caring brother, Dr. Bart A. Kummer, can attest. My own sincerest hope for all the efficiencies and increased access that the Affordable Care Act will bring is that it will make possible more doctors like my father and brother.

My eulogy, April 4, 2014:

When I was growing up, I didn't have a lot to say to my father. There wasn't a chance to say much. He was at the office or at the hospital, places that seemed extensions of our house--and that was intentional. One Ellington Avenue, that grand house he and Uncle Edwin converted to their offices, was as much a part of our natural childhood environment as the living room or den of the house my parents built--maybe more so. It didn't really matter that my mother refused to live over the office. He built our house so close to it we might as well have.

We were at the hospital, another grand mansion, almost as much, because the office and the hospital were the places we could see him. Just two weeks ago, coming out to the main entryway at the hospital, I asked the woman at the visitor desk something about my father. “Are you Bart?” she asked. “No,” I said. “Then you must be Cory. And how's Merle?” She told us about having been my father's patient since 1951, and about his delivering her four children. This was a woman I probably never met, yet she cared enough about my father to remember all three of our names except for one letter.

The whole community, then, was part of our family. And if it was sometimes difficult that the hospital line or office line seemed to ring more than the house line ever did—it was definitely a mixed blessing, having cool multi-line pushbutton phones all over the house—or that dinner was usually late while we got updates from his chief nurse as to when Doctor was coming home, we came to love the legacy that my father's devotion to his patients left us. It was a badge of pride then that we were Dr. Kummer's children. It is a badge of pride now.

That inaccessibility changed when my father acquired a partner in Neil Brooks, the signal event in his career, and suddenly became more available to us. Given our mother's increasingly debilitating illness, this couldn't have come at a better time. And for me, at least, it came when I was facing many of late adolescence's thorniest questions. I suddenly had a lot to say to my father. I'd never had any hesitation telling him anything personal--a doctor who has delivered half the town's children, been medical examiner, and heard the most intimate troubles of people from all walks of life, will be surprised by nothing.

As he was not. He intuited much of what I was going to say before I told him, and was always an utterly open, sympathetic, unjudging listener. What had once seemed perhaps a bit flat next to the scintillating wit and effervescent sparkle of our mother came to seem the most valuable quality in the world one person could give another, infinite patience and attention, and the most valuable assurance a parent could give a child: the certainty that however we screwed up, whatever happened to us, our father would always be unshakably for us, behind us, support us, and love us.

Another change happened, too, this one in me. After growing up wanting only to emulate my mother's sophistication, I saw that what I wanted to emulate even more was my father's natural gallantry. He accepted people for just who they were, and tried to meet them just where they were--even if that meant offering halting greetings in the many languages he fractured with the charming mashups that are still part of our family’s shared communication. I say "yo no say" and "va ben-e " without even meaning to, and in emails have introduced a generation of young writers to my father's "Hokay" with an "h." He could and did charm everyone by making it clear that he wasn't the type to judge. My father had flawless manners, because they were the result of true etiquette: not fussy form to demonstrate superiority but the wish to put others at ease.

As his capacities and memories started to slip, what remained was a distillate of the purest sweetness. Joan, our stepmother, started to bring that out in him when they met again soon after being widowed, and their life together had a marvelous companionability. It was a joy for us to see. Their marriage rivaled the happiness of our uncle and aunt--the easiest, most natural kind of match, built on humor, flexibility, tolerance, and a simple delight in each other's presence. We've been immeasurably enriched by Joan, whose wry, ready humor and plain wonderfulness will keep us smiling for we hope many years to come.

I told my father that he wasn't allowed to die until he'd tied his marriage record to our mother, and he listened: last December he and Joan celebrated their 30th anniversary. When I saw him in the hospital in January he had a bit of trouble remembering names, but he did say, accurately, "I've been married to two women, both for 30 years." Just the mention of his grandchildren’s names, and his great-grandson’s, would bring a broad smile to his face.

On that visit he wanted me to call the house to find out if my mother was home, the first time in the 33 years since she died that I'd ever heard him express that sort of confusion. No, I said. She's not going to answer. My phone rang, and when I hung up I said, That wasn't her, either. (Actually, I said, "That wasn't she." My father is probably correcting me now.) When I left the hospital, a few hours later, I quizzed him on who I was going to visit when I went to the house, the kind of current-facts quiz I popped fairly mercilessly. He said "Joan," and I said I'd tell her how many times he'd asked after her. He laughed delightedly--the most typical reaction he had to his own spotty memory, or to some unseen obstacle that his wonderful caretaker, B, would help him overcome. Even when he seemed to be staring into the distance while we were telling long and involved stories and not even trying to help him follow, just when I would lob in a sly punch line he'd let out a sharp burst of laughter. This happened time and time again. His humor never faded.

In the last few months, Joan reported that he would tell her he was going down to Wallingford after lunch to see his parents. He cheerfully told Bart he was leaving on a trip, but he wasn't sure where or how he was going to get there. These mentions, along with his declining health, seemed fairly clear signs that he was getting ready to leave us. But as Joan would say, slipping her hand into his warm grasp and seeing the warm, beaming smile he gave her right until the moment he died, "He's just so adorable. I never want him to go." We didn't either.

Original article, December 17, 2009:

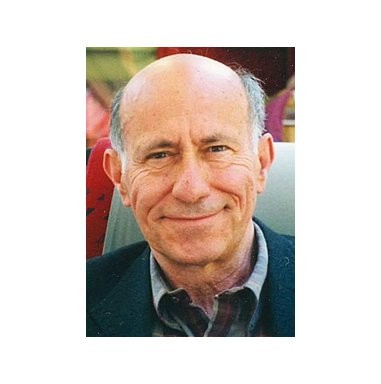

Photo Courtesy of Dr. Bart Kummer

A few weeks ago I got the kind of morning call nobody wants to, especially after you've just gotten off two long plane trips to long-planned engagements: my sister saying our father had just had a stroke and was on his way to the hospital. Don't come, she said. She was driving from Boston to the hospital in Hartford he was being taken to; my brother, a gastroenterologist in New York, was driving up at the same time.

The story had a happy ending, and not just because I'm lucky enough to have such concerned and proximate siblings, one of them a superb diagonistican and a tenacious advocate for all his patients, let alone for his father. It was because my father--a longtime family practitioner who knew he was at high risk of stroke and had no desire to live an impaired life--keeps by his bedside a note asking to be given t-PA, a powerful clot dissolver. If administered within a few hours of the first symptoms, t-PA can break up clots before they choke off blood supply in the brain, causing the kind of permanent damage my father feared.

The drug, which is given intravenously, has been in wide use for just 15 years, and the risk of causing hemorrhage is so great that either the patient or a health-care proxy must give permission for it to be used. So my father had my stepmother, Joan, write out a note saying that in the event of a stroke he wanted to get t-PA as soon as possible, and authorized its administration.

No one can say whether his stroke would have been the calamity he feared without t-PA. But he feels he dodged a bullet, and we all do too.

He was fortunate in many respects. He was not regularly taking a powerful blood thinner, which can make t-PA too dangerous, as it can cause uncontrollable hemorrhaging. Because his medical history included the minor events called transient ischemic attacks, which are often harbingers of stroke, he and his doctors knew he was at high risk for an actual stroke, and that the cause would likely be clotting rather than hemorrhaging. The distinction is crucial, because t-PA can drastically accelerate a hemorrhagic stroke, the hallmark symptom of which is an overwhelming headache. In his case, he awoke with tingling in his right arm, trouble moving his hand, and some speech slurring. "I knew damn well I was having a stroke," he told me a few days later when I visited him at St. Francis Hospital.

He'd asked to be taken to St. Francis, one of two Hartford hospitals with stroke centers, because he had been an intern there in 1949, in what was then a brand-new building. It felt like "old home week," he told me, adding that he was very glad to be in a much newer building. His mood was and remains as cheerful as he's ever been--understandable, given that his minimal speech slurring (his ability to find words was luckily not affected, only his motor skills) and trouble moving his right hand are responding well to physical therapy.

No one can say whether his stroke would have been the calamity he feared without t-PA. But he feels he dodged a bullet, and we all do too. I'm even glad he can still tell me clearly that I should have gone to medical school.

My spouse, John Auerbach, is the health commissioner of Massachusetts, and happened to mention the story to a stroke specialist he met at a meeting, Dr. Lee Schwamm, a neurologist who directs the acute stroke and telestroke center at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Schwamm was not just charmed by the story: he thought that other patients could and should benefit from it, by discussing their eligibility for t-PA with their doctors and keeping similar instructions in their wallets or by their bedsides. My father was able to tell the emergency medical technicians who came within minutes that he needed to go to a stroke center; "Give me t-PA," he told them, and apparently every person he encountered at the hospital. Not all patients will be so lucky as to be able to speak. And there might be no health-care proxy available to authorize administration of the drug.

Minutes count, as this dramatic account by Richard Knox, the health reporter for NPR, shows. In it a 49-year-old woman shrugs off tingling in her arm until she and a nurse friend she calls realize she needs emergency treatment; though the hospital is 75 miles away from Mass General, direct links to the hospital and to an on-call doctor's home, in which the doctor quizzes the patient to determine exactly when the stroke began, enable her to get t-PA at exactly the last minute she is eligible. It's suspenseful and incredible to hear.

Knox also liked the story of my father, and posted a piece about it on NPR's health blog, with a picture taken by my brother. I offer it here in hopes it can help someone in your life--and with great, and general, gratitude.